EDA

EDA in R - Introduction

This corresponds to the DataCamp Exploratory Data Analysis in R course.

It helps us understand how multiple variables are related to each other.

Concepts

Marginal: the chance that of an event happening.

Example: what are the chances of a heads on a coin flip, given that we

had just had a head. It is still 50%.

Conditional: If A, then the proportion of B changes.

Example: If a person is a man, then they are more likely to be tall.

Step 1: Understand your data

Check field types and values

First we want to make sure that we understand our data. Begin by visually scanning the table.

Then, use some functions to show what values are present in the data.

library(tidyverse)

t <- tibble(x = 1:10, y = rep(c('A', 'B'), 5) )

# Show the field types

str(t)## tibble [10 × 2] (S3: tbl_df/tbl/data.frame)

## $ x: int [1:10] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

## $ y: chr [1:10] "A" "B" "A" "B" ...# Show a summary of the values

summary(t)## x y

## Min. : 1.00 Length:10

## 1st Qu.: 3.25 Class :character

## Median : 5.50 Mode :character

## Mean : 5.50

## 3rd Qu.: 7.75

## Max. :10.00# Alternatively, this is a better way of showing if you have a lot of variables

# It uses the map function to apply summary to each field in t

# map(t, summary)# Useful for categorical variables and getting a breakdown of the values

table(t$y)##

## A B

## 5 5# Also useful is unique(t$y)Visualize Categorical data

Categorical data is generally stored as text values. They can be encoded with numbers, but there should be no significance to the range between different values.

Examples of categorical data would be:

- Gender (m/f)

- State (WV, CA, …)

- Grade level

- Zipcode

Clean unique values

Start by evaluating for bad categories or na values.

library(tidyverse)

# Bad tibble

t_raw <- tibble(

person = c('Bob', 'Bob', 'Bob', 'Sue', 'Sue', NA, 'Su'),

group = c('Group A', 'Group B', 'A', 'a', 'b', NA, ''))

# Fixes stored as data, rather than code.

t_fix = tibble(

from = c('Group A', 'Group B', 'A', 'a', 'b' ),

to = c('a', 'b', 'a', 'a', 'b')

)

# Simple fixes

#

# Clean up with filter / mutate

# Use !is.na to only return fields with values

# Use "" to filter for blank fields

# Use mutate and ifelse to convert from bad values to good values

t1 <- t_raw %>%

filter(!is.na(person),

!is.na(group),

group != '') %>%

mutate(person = ifelse(person == 'Su', 'Sue', person))

# Join fix

t2 <- t1 %>%

left_join(t_fix, by = c('group' = 'from')) %>%

mutate(group = to,

to = NULL)

print(t2)## # A tibble: 5 × 2

## person group

## <chr> <chr>

## 1 Bob a

## 2 Bob b

## 3 Bob a

## 4 Sue a

## 5 Sue bFind unique items and counts

Remove or group low-count items. View both absolute count and proportions

library(tidyverse)

# Change printout to simplify output

options(scipen = 999, digits = 3)

t <- tibble(x = c('Bob', 'Bob', 'Bob', 'Sue', 'Sue', 'Dave', 'Bob'),

region = c('A', 'B', 'B', 'A', 'A', 'B', 'C'))

# Print normal table

table(t$x, t$region)##

## A B C

## Bob 1 2 1

## Dave 0 1 0

## Sue 2 0 0# remove

t_fixed <- t %>%

filter(!x %in% c('Dave', 'Bob'))

# Print table of % (of total)

# For 2nd argument,

# NA: % of total

# 1: % of row

# 2: % of column

prop.table(table(t$x, t$region))##

## A B C

## Bob 0.143 0.286 0.143

## Dave 0.000 0.143 0.000

## Sue 0.286 0.000 0.000Convert text into numeric variables

Convert textual values into numbers, where it makes sense with the underlying data.

library(tidyverse)

# Bad tibble

t_raw <- tibble(

sales_rank = c('Rank 1', 'Rank 2', 'Rank 3'),

level = c('a', 'b', 'c')

)

# Conversion table or ifelse

t_fix = tibble(

from = c('a', 'b', 'c'),

to = 1:3

)

t1 <- t_raw %>%

mutate(sales_rank = as.numeric(substr(sales_rank, 6, 6)))

# Join fix

t2 <- t1 %>%

left_join(t_fix, by = c('level' = 'from')) %>%

mutate(level = to,

to = NULL)

print(t2)## # A tibble: 3 × 2

## sales_rank level

## <dbl> <int>

## 1 1 1

## 2 2 2

## 3 3 3Charts

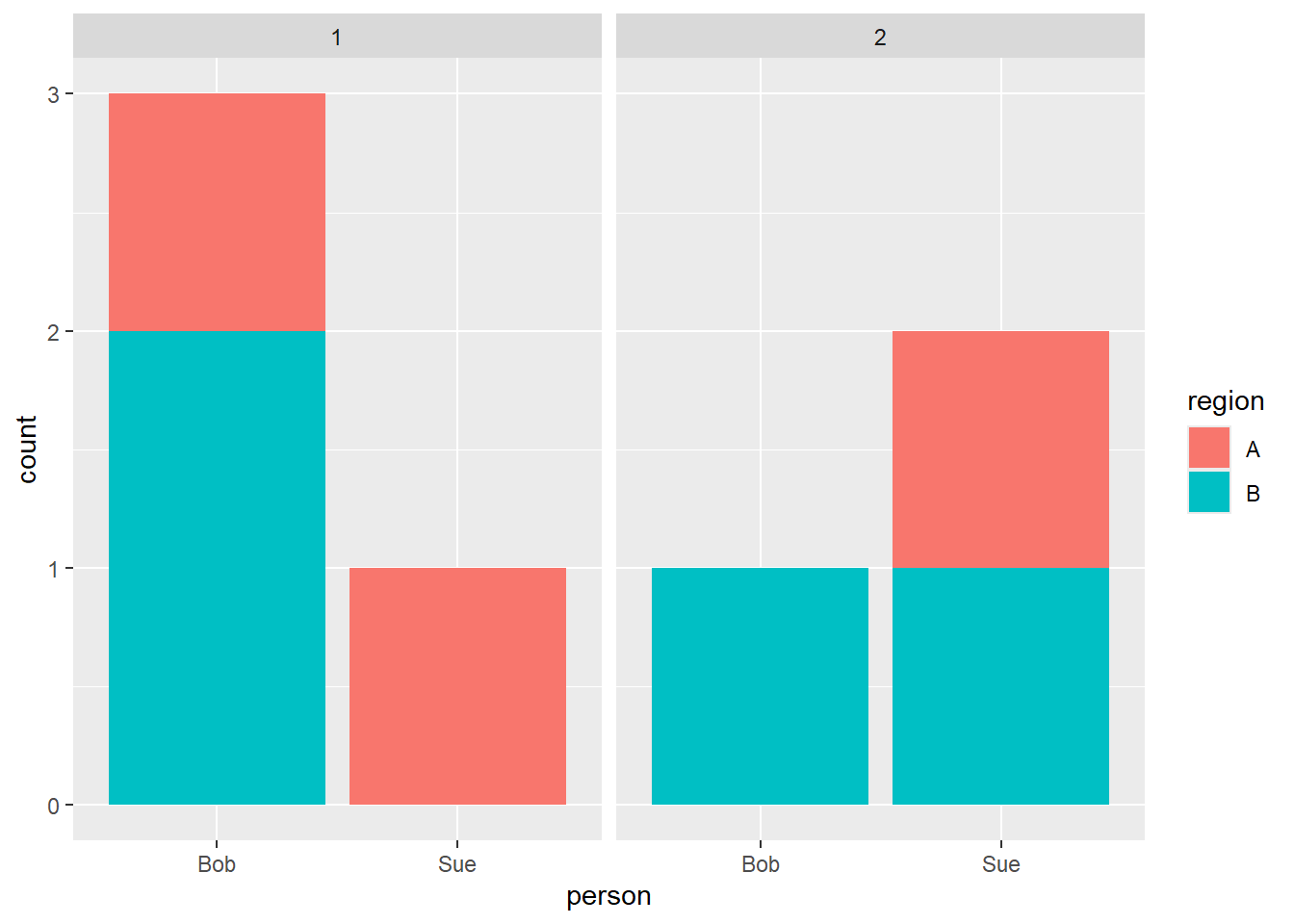

Bar charts are very useful for categorical data. You can show the basic value as the x or the y, and then use color or facets to break down further categories.

library(tidyverse)

t <- tibble(person = c('Bob', 'Bob', 'Bob', 'Sue', 'Sue', 'Sue', 'Bob'),

region = c('A', 'B', 'B', 'A', 'A', 'B', 'B'),

year = c(1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2))

ggplot(data = t) +

geom_bar(mapping = aes(x = person, fill = region)) +

facet_wrap( ~ year)

Vizualize Continuous data

Continuous data is numeric information, where the difference between values is meaningful. You can typically measure this data at different levels of precision (ie., age in years, age in months, age in days, …)

Examples:

- Weight

- Price

- Height

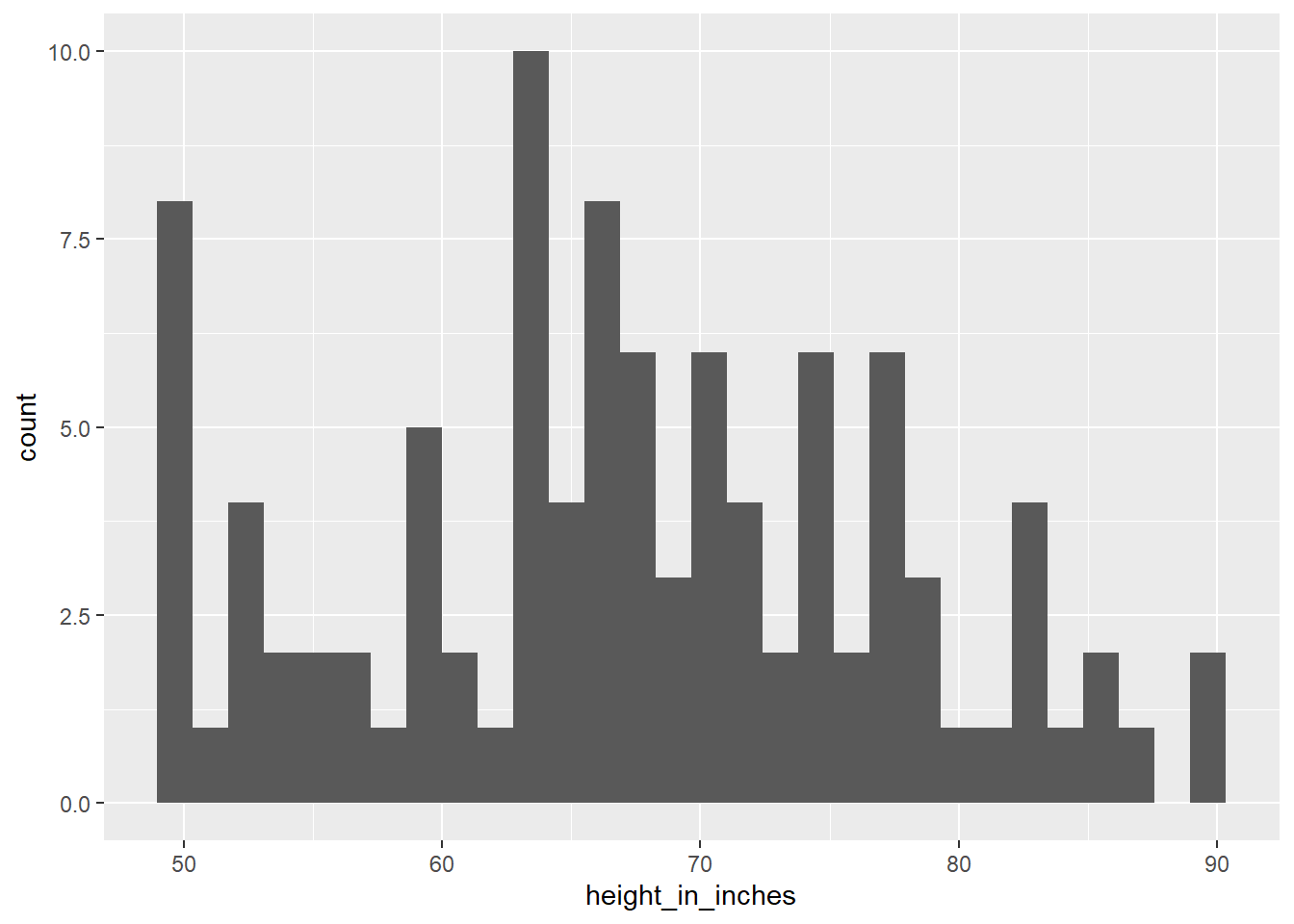

Remove outliers

We often have to clean up values.

Start by looking at the data with a histogram to get a general idea of its shape. Think about if it appears to have a normal distribution.

You may have to eliminate outlier values, or add a log transform to the data.

library(tidyverse)

# Generate a normal distribution of data

t_raw <- tibble(id = 1:100,

height_in_inches = rnorm(n = 100, mean = 5.5*12, sd = 12))

# Eliminate outlier values

t <- t_raw %>%

filter(height_in_inches > 50,

height_in_inches < 90)

# Or, set outlier values to a max or min value to avoid removing them from the dataset.

t <- t_raw %>%

mutate(height_in_inches = ifelse(height_in_inches < 50, 50, height_in_inches),

height_in_inches = ifelse(height_in_inches > 90, 90, height_in_inches))

ggplot(data = t) +

geom_histogram(mapping = aes(x = height_in_inches))

Zero-inflation strategy

We often have issues with variables having a lot of zeros. We can convert that into a yes/no variable. Sometimes it is more important to have a yes/no variable than an actual amount.

library(tidyverse)

# Generate a normal distribution of data

t_raw <- tibble(person_id = 1:10,

amount_won_in_game = c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 100, 200, 140, 20, 0))

# Create yes/no

t <- t_raw %>%

mutate(winner01 = ifelse(amount_won_in_game > 0, 1, 0))

table(t$winner01)##

## 0 1

## 6 4Step 2: Correlations

We typically want to understand cause and effect in our dataset.

Correlation

cor

Cause/effect is typically started with some type of correlation table. However, we have to be careful about blinding trusting this table. It can be very misleading, as well as require some setup.

library(tidyverse)

t_raw <- tibble(x = c(0,0,0,0,0,0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 ),

y = c(10, 10, 9, 8, 7, 9, 10, 100, 20, 100, 80, 28),

region = rep(c('A', 'B'), times = 6))

# Fix region by converting it into a 01 value.

t <- t_raw %>%

mutate(regionA01 = ifelse(region == 'A', 1, 0))

# It's usually good to make a tibble for the cor test with only numeric values

t_numbers <- t %>%

select(where(is.numeric))

# Show all figures

cor(t_numbers)## x y regionA01

## x 1.000 0.663 0.000

## y 0.663 1.000 -0.277

## regionA01 0.000 -0.277 1.000cor.test

The cor.test function will show the statistical significance of any correlations you find.

library(tidyverse)

t_raw <- tibble(x = c(0,0,0,0,0,0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 ),

y = c(10, 10, 9, 8, 7, 9, 10, 100, 20, 100, 80, 28),

region = rep(c('A', 'B'), times = 6))

# Fix region by converting it into a 01 value.

t <- t_raw %>%

mutate(regionA01 = ifelse(region == 'A', 1, 0))

# It's usually good to make a tibble for the cor test with only numeric values

t_numbers <- t %>%

select(where(is.numeric))

# Show the correlation's statistical significance

cor.test(t_numbers$x, t_numbers$y)##

## Pearson's product-moment correlation

##

## data: t_numbers$x and t_numbers$y

## t = 3, df = 10, p-value = 0.02

## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.143 0.896

## sample estimates:

## cor

## 0.663Correlation chart

ggcorrplot is a nice library for printing correlation tables

library(tidyverse)

library(ggcorrplot)

t_raw <- tibble(x = c(0,0,0,0,0,0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 ),

y = c(10, 10, 9, 8, 7, 9, 10, 100, 20, 100, 80, 28),

region = rep(c('A', 'B'), times = 6))

# Fix region by converting it into a 01 value.

t <- t_raw %>%

mutate(regionA01 = ifelse(region == 'A', 1, 0))

# It's usually good to make a tibble with only numeric values

t_numbers <- t %>%

select(where(is.numeric))

# Show the correlation's statistical significance

ggcorrplot(cor(t_numbers),

colors = c('red', 'white', 'blue'))

Plot Correlations

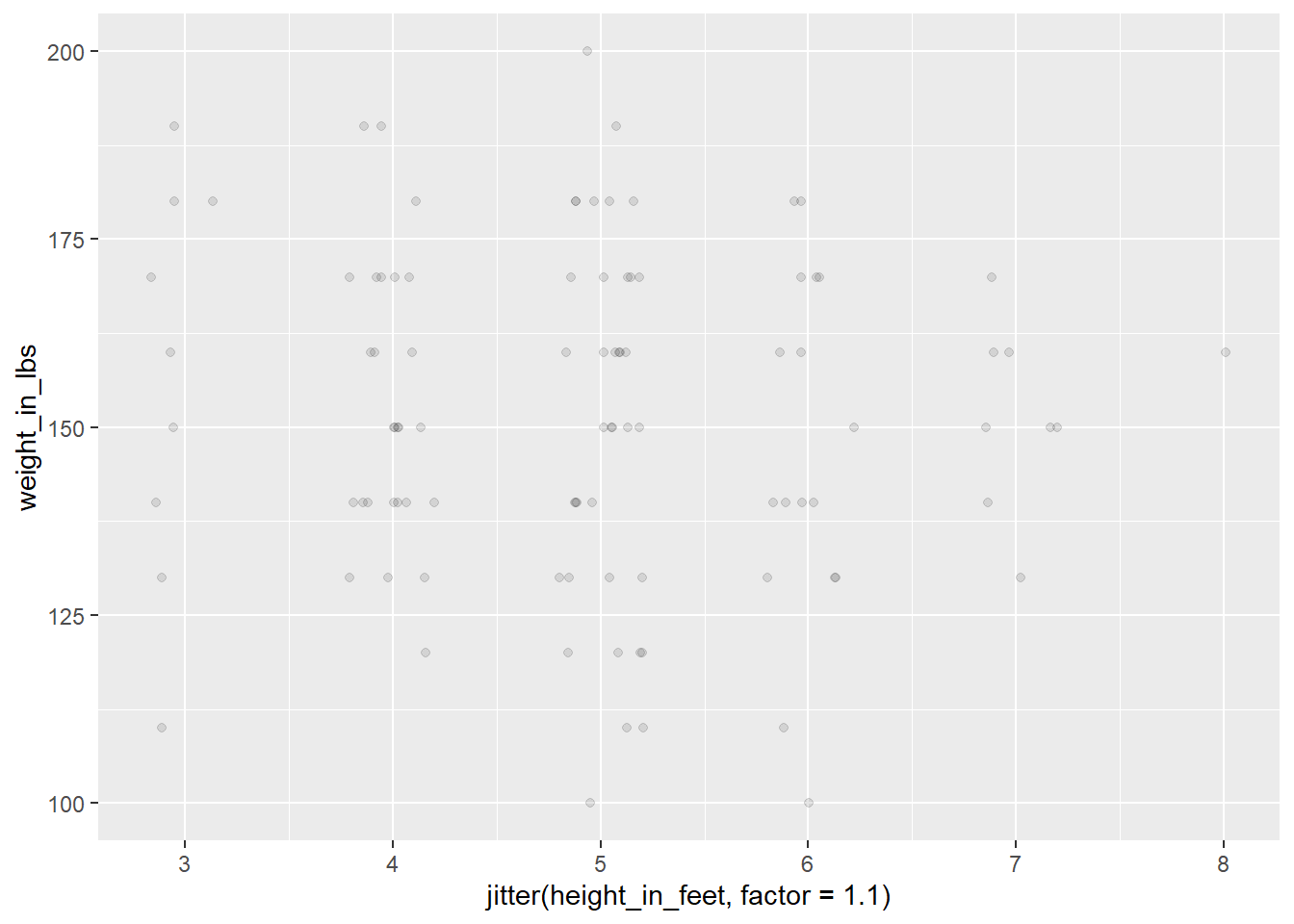

Point Chart (continuous, n < 100)

After we see a connection between our variables, you should plot the relationship.

Point plots are pretty good for small to mid-size datasets. However, we will get issues with overplotting. There are two general mitigations:

- Set alpha to a low value

- Add jitter

library(tidyverse)

# Generate a normal distribution of data

t <- tibble(height_in_feet = round(rnorm(n = 100, mean = 5, sd = 1), 0),

weight_in_lbs = round(rnorm(n = 100, mean = 150, sd = 20), -1),

)

ggplot(data = t) +

geom_point(mapping = aes(x = jitter(height_in_feet, factor = 1.1),

y = weight_in_lbs),

alpha = 0.1)

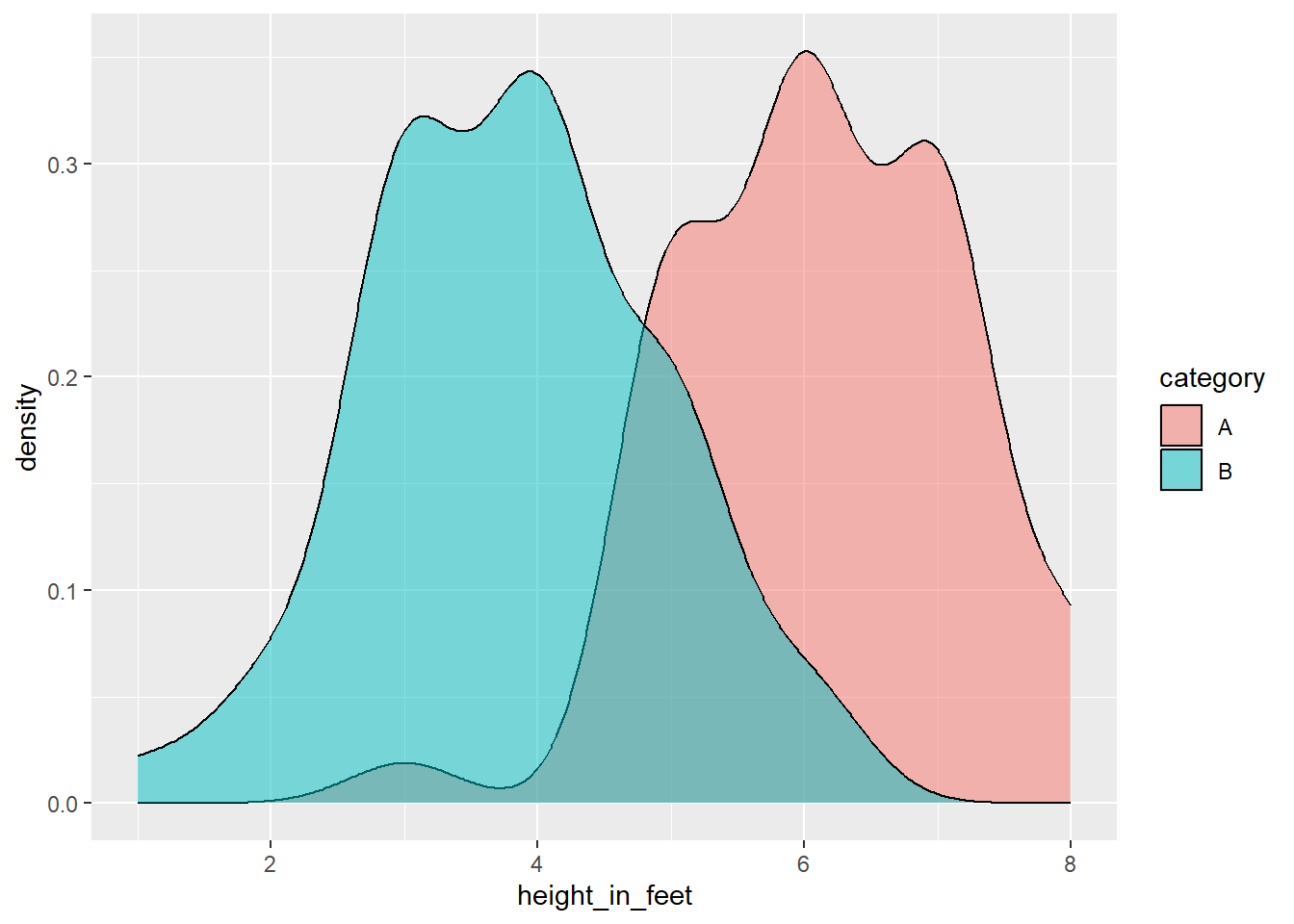

Density Chart (categories, n > 200)

At a certain point, you should shift to a density plot, which is basically a nicer histogram.

library(tidyverse)

# Generate a normal distribution of data

t <- tibble(height_in_feet = round(rnorm(n = 100, mean = 5, sd = 1), 0),

category = rep(x = c('A', 'B'), time = 50))

# Make the plot more interesting by changing group A

t <- t %>%

mutate(height_in_feet = ifelse(category == 'A', height_in_feet + 1, height_in_feet - 1))

ggplot(data = t) +

geom_density(mapping = aes(x = height_in_feet,

fill = category),

alpha = .5)

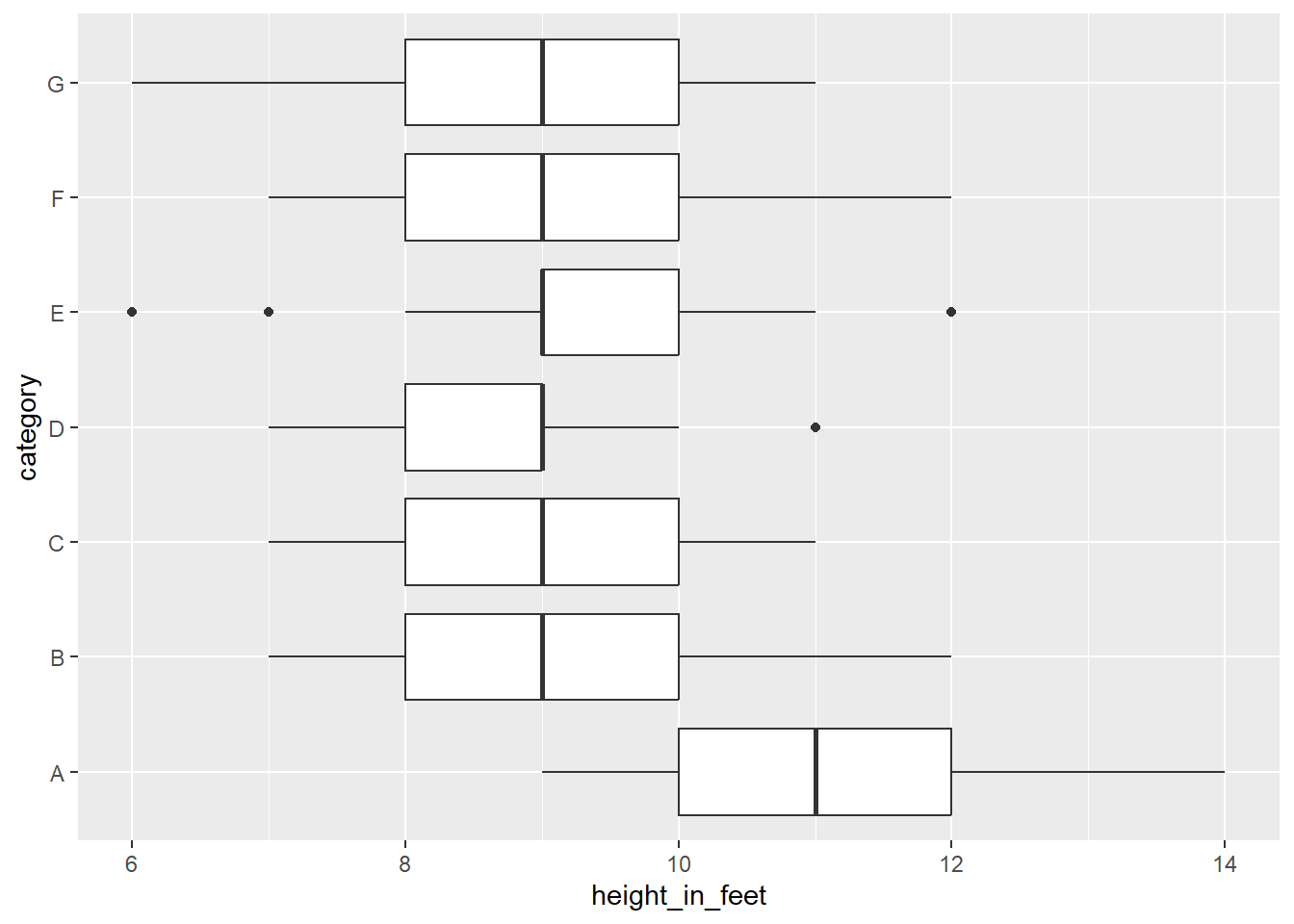

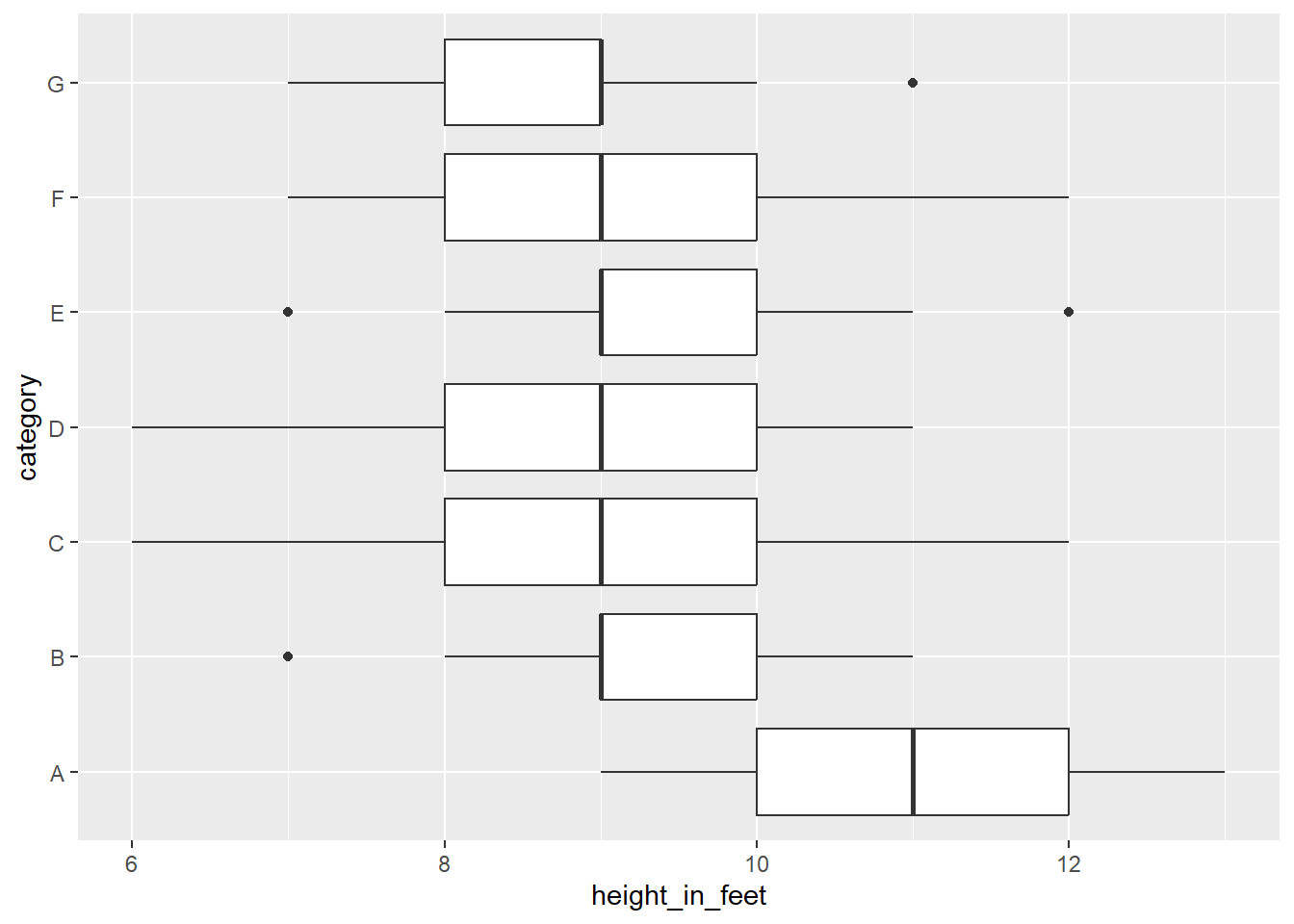

Boxplot Chart (categories, n > 2,000)

At a certain point, you should shift to boxplots. Add both a x and y scale, and use facets as needed.

library(tidyverse)

# Generate a normal distribution of data

t <- tibble(height_in_feet = round(rnorm(n = 700, mean = 10, sd = 1), 0),

category = rep(x = c('A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G'), time = 100))

# Make the plot more interesting by changing group A

t <- t %>%

mutate(height_in_feet = ifelse(category == 'A', height_in_feet + 1, height_in_feet - 1))

ggplot(data = t) +

geom_boxplot(mapping = aes(x = height_in_feet,

y = category))